Bushwhacking and workshopping: Creating hiking trails in China’s Giant Panda National Park

By Miranda Li

As I pushed aside yet another bamboo leaf threatening to cut my face, I thought, bushwhacking through face-high bamboo is probably the hardest bushwhacking I’ve ever done. The “trail” was a series of footprints left by the local ranger Zhao on a steep 50-degree surface. One slip and I would go tumbling down into the muddy bamboo forest.

Thick bamboo forest near Feishui Village, Dayi County, Sichuan (photo by Miranda Li)

Our small team was in the forest to scout out hiking routes in Giant Panda National Park near Yunhua and Feishui Villages in Dayi County of Sichuan. We were mapping out potential environmental education hiking trails, and planning visitor routes that had minimal environmental impact, had high educational value, and brought economic benefits to the local community.

Background on China’s national parks system

When I came to China in 2021, I was surprised to learn that it only has, as of now, five official national parks. They were announced at COP15 in October 2021: Three River Source, Giant Panda, Hainan Tropical Rainforest, Wuyi Mountain, and Northeast Tiger and Leopard National Parks.

Source: CGTN

As a young child, my family and I traveled to places labeled as “national parks” that were in reality forest parks, geoparks, wetland parks, scenic areas, and so on. One piece of land could even be under the jurisdiction of two different administrations, creating management and governance confusion; a 2020 study by Sheng et. al found that about 10% of the total protected area in Yunnan was “designated under multiple categories and simultaneously managed by more than one institution.” The national parks system aims to consolidate management and solve the issues of “九龙治水” or “nine dragons ruling water,” in order to benefit both protection and visitation.

Although relatively new, China’s national parks system was not started from scratch. Many of the areas in the national parks are former protected areas; for example,the basis of Giant Panda National Park is the combination of over 60 different giant panda reserves and other nature reserves across Sichuan, Gansu, and Shaanxi.

The national parks system is vital to both conservation and development efforts in the country. In terms of conservation, the new protected areas system with national parks as the “mainstay” will be crucial to reaching 30×30 goals as laid out in target 3 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (protect 30 percent of the world’s land and water by 2030). In particular, the system protects areas with rich biodiversity, including many endangered animals endemic to China.

In terms of development, it is important that the national parks administration works with local government and community organizations, and that local areas benefit first and foremost from the creation of the national parks.

Importantly, all the work is done in partnership with local governments and local communities, so that after initial funding, training, and partnership, locals can take ownership of the initiative, and as a result ownership of the benefits and profits that it brings.

Developing hiking trails

A month after my initial scouting visit to Feishui and Yunhua Villages in Giant Panda National Park, I came back to Yunhua with my colleague 海燕 (“Hai Yan”) and a talented team of three volunteers: 玉容 (“Yu Rong”), a flora expert and a close friend of mine from my time in Xishuangbanna; 方方 (“Fang Fang”), a designer from Xi’an; and 小郭 (“Xiao Guo”), an energetic college student and former Shan Shui intern, as well as two environmental education experts: 梅子 (“Mei Zi”) and 凌琴 (“Ling Qin”).

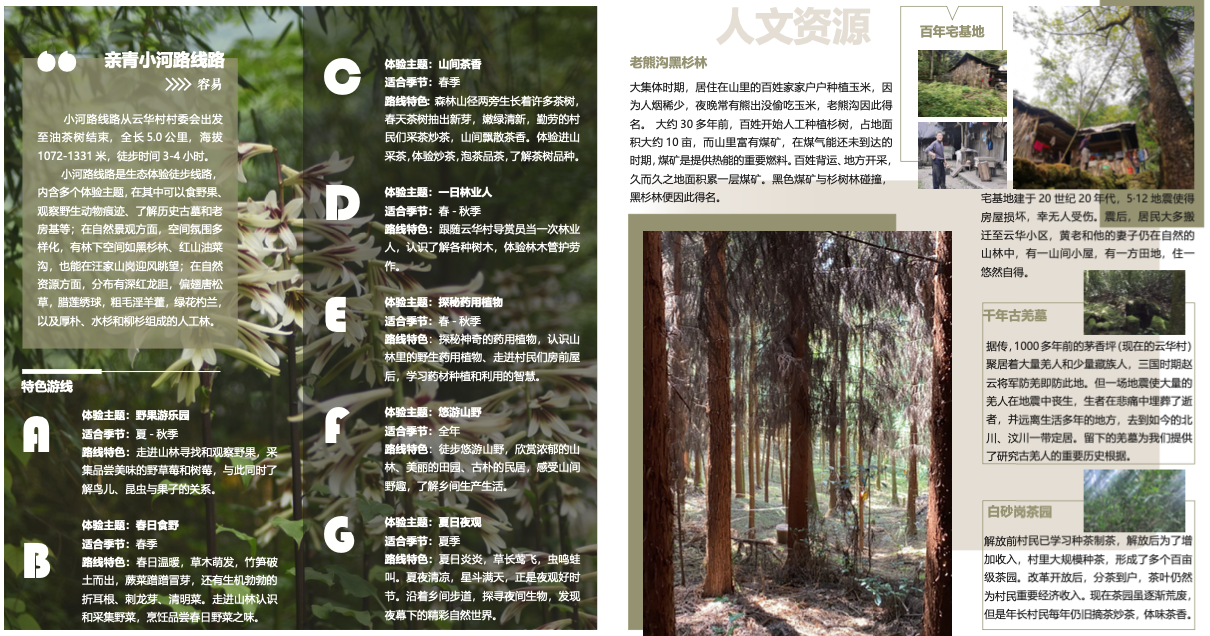

Along a hiking trail in Yunhua Village (photo by Miranda Li)

Our goal was a simple one: work with local rangers to design hiking routes near Yunhua Village, and create a brochure describing the routes and local flora and fauna that the community can use as a basis to hold their own environmental education programs.

On the first day, we worked with Party Secretary Jing, Vice Party Secretary Qiu, and park rangers to come up with a plan for the most promising routes to walk. These routes were already local patrol routes and farmers’ transport routes; unlike the previous month’s scouting trip, we would avoid thick bamboo forests and routes that needed a lot of repair and maintenance to become a hiking trail.

Together, we decided on the key information to record for each route: navigation and direction, accessibility, ecological integrity, historical and cultural landmarks, scenic value, flora and fauna, local stories, and potential risks. We divided into small teams by topic, each comprised of at least one local ranger and one member of the Shan Shui team.

Hai Yan leading a workshop in Yunhua Village (photo by Ling Qin)

During the days, we hiked the trails, led by local community leaders, Liu and Chen. Along the route, a local ranger, brother Zhang, explained the various flowers and plants we saw. They talked about which ones were edible – huanglian root, giant knot weed, palm cores, tea leaves – and we even tasted some ourselves. Yu Rong, our flora expert, supplemented brother Zhang’s descriptions with her own stories and ways of remembering the plants’ names and key characteristics.

Local community leaders Chen and Liu leading the way (photo by Miranda Li)

Trying edible giant knot weed (photo by Ling Qin)

For the rangers, these trails are their childhood homes. Hearing their stories of how they grew up running through the forests, foraging and playing, observing animals and their traces like footprints, dung, bird feathers, and porcupine spikes, it became clear to us that there is so much to be learned from spending time with them. Our position as “outsiders” was to work with the local forest rangers, village representatives, and government officials to bring their knowledge to life, and share it with the world.

Listening to stories (photo by Ling Qin)

Hai Yan loved to find leeches (photo by Ling Qin)

After each hike, we met in the local government building, split into our small topic groups, and organized and compiled our observations and recordings. Fang Fang and community leaders Liu and Chen drew the route and key landmarks; Yu Rong and Li Wenjie, a local resident and plant expert, wrote out the names of all the plants and animals we had seen, including both the standard Mandarin name and local name; Xiao Guo and Brother Zhang compiled the legends and stories about Yunhua; Hai Yan and Ranger Zhao recorded key risks and dangers along the route.

Drawing out the hiking route and landmarks along the way (photo by Miranda Li)

Yu Rong working with local rangers to identify photos they took of local flora and fauna (photo by Miranda Li)

As I saw everyone working together in their small teams, excitedly compiling information about Yunhua Village, I thought, this is how a hiking trail should be designed: supplementing the passion, stories, and local knowledge of the local rangers with the professional knowledge of outside experts.

Small groups presenting their findings (photo by Miranda Li)

We left Yunhua Village with our hearts full and a car full of information compiled by our small teams. Over the next months, we continued to collaborate in these small groups. Together, we memorialized the information into two hiking trails in Yunhua, trails that future visitors to Giant Panda National Park can come and experience for themselves.

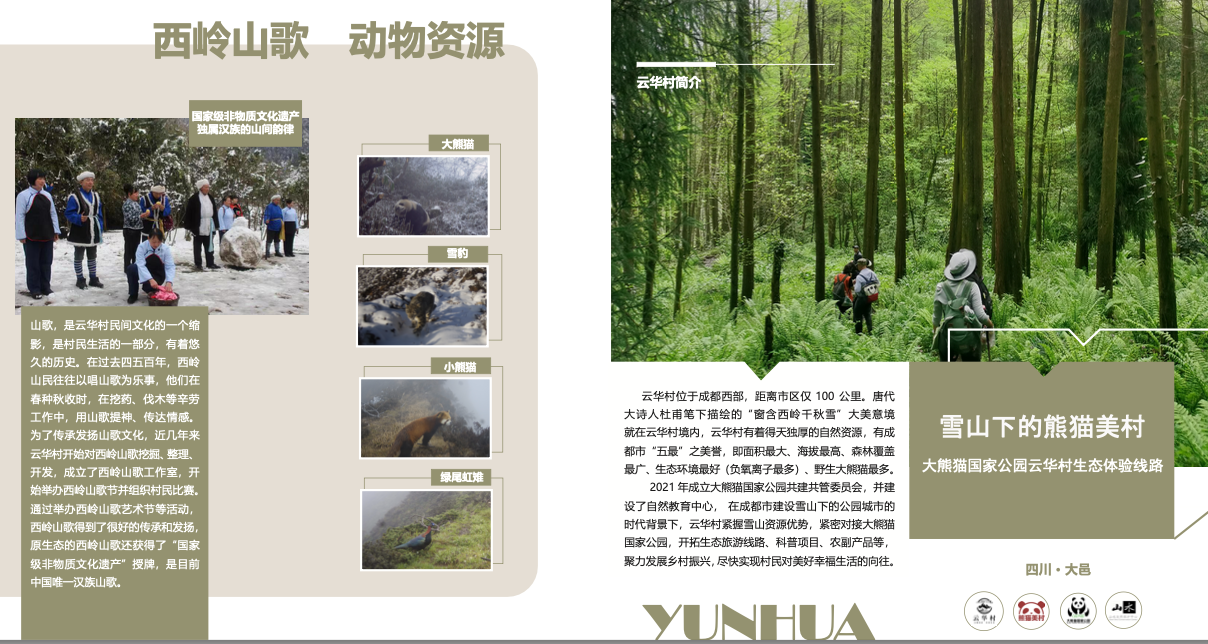

Snippets from the Yunhua Village hiking brochure (from Fang Fang)

On the last page of the brochure introducing the trails were the names of all the rangers, above our own. In a sense, the trails were “theirs,” and will always continue to be.

Concluding thoughts

Team photo (photo by Hai Yan)

Today, visitors who come to Giant Panda National Park here in China will not have the same experience as if they visit, for example, a national park in the US. They will not be handed a brochure at a large gate explaining the visitor centers, hiking routes, camping information, and so on. Outside of areas that were already developed as tourist areas before the establishment of the national park, most of the hikes they go on will not be nicely labeled with directions and information boards about local flora and fauna.

As China’s national parks system grows rapidly, from five today to potentially 49 by 2035 as laid out in the 2023 National Park Spatial Layout Plan, eco-tourism, environmental education, and outdoor sports like hiking, camping, rafting, and rock climbing will be a key part of shaping the role of national parks in the Chinese psyche and spirit.

Through providing ecological experiences, national parks can improve nature and conservation awareness, as well as health and well-being. They will be an important source of education for people from the local villages, from China’s large cities, and even from outside the country.

Importantly, the development of these types of experiences, such as hiking routes in national parks, should be done in partnership with local communities. After all, “人与自然和谐共生” or the “harmonious existence of humans and nature” is something that truly makes China’s national parks unique.

In our week in Yunhua Village working with local rangers, we experienced this harmony first-hand. I hope that as China expands its national parks system, this harmonious relationship will be preserved and celebrated across the country.