China-Europe Policy Dialogue on OECMs Seminar Report

In the grand narrative of global biodiversity conservation, Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs) are gradually emerging and gaining increasing attention. On May 15th, the China-Europe Policy Dialogue on OECMs Seminar was held in Beijing to discuss new approaches to biodiversity conservation. Representatives from government departments, academia, conservation organizations, and international organizations, including experts and practitioners in the field of biodiversity, participated in the meeting. Through keynote speeches and roundtable dialogues, participants shared and exchanged practical experiences in promoting OECMs in China and Europe and explored the implementation pathways and strategies for OECMs in China’s forestry and grassland authority.

This seminar, as the launching event of the OECMs policy dialogue project supported by the China Biodiversity Facility (CBF), which is funded by the European Union and implemented by Agence Française de Développement (AFD), was jointly organized by the Shan Shui Conservation Center and Peking University Center for Nature and Society, partnering with Tsinghua University National Parks Research Institute, the Chinese Academy of Forestry, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Shan Shui Foundation, and the Agence Française de Développement (AFD). The China Biodiversity Facility (CBF) is an important platform for China-Europe cooperation in the field of biodiversity, aiming to promote public policies and practices for biodiversity conservation in China through innovative demonstration projects and policy dialogues. Shan Shui Conservation Center and IUCN jointly implement the OECMs policy dialogue project supported by CBF, aiming at promoting the implementation of OECMs in China through the assessment of the current situation of OECMs in China, China-Europe policy dialogues, and international experience exchanges.

Seminar venue

Seminar venue

OECMs: A New Tool for Biodiversity Conservation

Under the dual challenges of global biodiversity loss and climate change, biodiversity conservation has become a focus of international attention. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) has set the ambitious goal of protecting at least 30% of terrestrial, inland water, coastal, and marine areas by 2030 (the 30×30 Target). However, protected areas have limitations in terms of coverage, and relying solely on protected areas is insufficient to achieve the 30×30 Target. Meanwhile, many areas outside protected areas are effectively conserving biodiversity through various means. In this context, OECMs have emerged as a new type of conservation tool, serving as a complement to protected areas and offering new approaches for achieving global biodiversity conservation targets.

OECMs refer to areas outside the protected area system that achieve long-term and sustained conservation of biodiversity through effective governance and management. These areas may be managed by governments, communities, NGOs, corporates, or private entities and cover a variety of ecosystem types and governance modes. Shi Xiangying, Executive Director of Shan Shui Conservation Center, noted in her opening remarks that OECMs, with their unique flexibility and inclusiveness, provide a new solution for recognizing and supporting conservation contributions from outside protected areas and from multiple stakeholders. Since the concept of OECMs was officially determined at CBD COP14 in 2018, global attention to OECMs has been on the rise.

Shi Xiangying delivered opening remarks

Khalid Pasha, IUCN Asia Regional Office, Regional Coordinator, Protected, Conserved, and Heritage Areas, noted in his opening remarks that countries around the world are actively promoting OECM initiatives. Many Asian countries, including China, have already begun to pilot and implement OECMs through various approaches. He expressed the hope that China-Europe policy dialogues will facilitate the exchange of experiences, promoting OECMs as a cornerstone of inclusive and effective conservation, thereby contributing to the achievement of global biodiversity conservation goals.

Khalid Pasha delivered opening remarks

Current Status and Contributions of OECMs

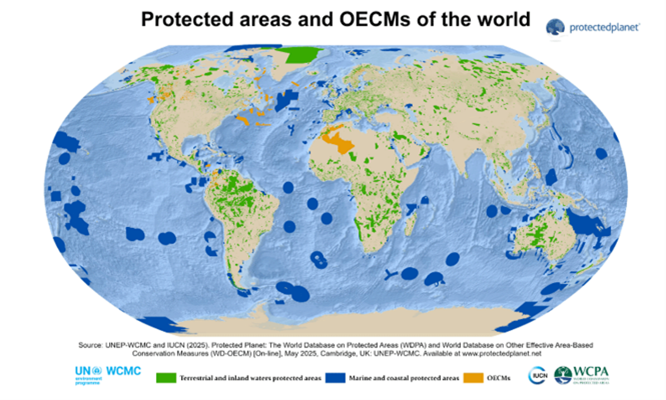

The World Database on OECMs (WD-OECM) on the Protected Planet website is the authoritative global data source for OECMs. Heather Bingham, Senior Programme Officer of the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC), introduced the current status of OECMs globally and regionally in the WD-OECM database. As of May 2025, WD-OECM has recorded 6,479 OECMs from 14 countries and regions, with 353 OECMs in the Asia-Pacific region from countries such as the Philippines, South Korea, Japan, and Bhutan. In Europe, OECM data mainly comes from Sweden and Guernsey. The inclusion of 10 OECMs in Guernsey increased terrestrial conservation coverage from 4% to 11%, while the inclusion of 5,365 OECMs in Sweden increased it from 15.5% to 15.7%. These OECMs not only fill conservation gaps and increase conservation coverage, but also play an important role in enhancing the coverage of important biodiversity areas and improving ecological connectivity of protected and conserved area network.

Global Protected Areas and OECMs Map (Protected Planet website, picture from Heather Bingham’s slides)

|

Supplementary Note: The Protected Planet website, jointly managed by UNEP-WCMC and IUCN, collects and shares data on protected and conserved areas worldwide. It includes the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), the World Database on OECMs (WD-OECM), and the Global Database on Protected Area Management Effectiveness (GD-PAME). It aims to support information-based decision-making and conservation planning and provides a basis for monitoring and reporting progress towards international environmental goals, helping to track headline indicators of the 30×30 Target. With a wide range of data sources, it currently has over 400 data providers, including national governments, conservation secretariats, private actors, indigenous peoples, and local communities, covering 244 countries and regions globally. |

Heather Bingham shared several sets of data: currently, OECMs overlap with 189 Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs), including 121 (about 1%) KBAs that are partially or fully covered by OECMs but not by protected areas. In terms of ecological connectivity, 8.5% of the global land is both protected and connected. However, without OECMs, this proportion would drop to 7.5%. By forming OECM networks that complement existing protected area networks, the connectivity of the conservation network can be effectively enhanced, while also increasing the representation of different ecosystems and species.

Heather Bingham introduced protected planet platform and WD-OECM

Marine Deguignet from IUCN Global Team for Protected and Conserved Areas noted that the identification and recognition of OECMs should be grounded in the broader landscape and seascape for comprehensive consideration. Spatial conservation planning (SCP) helps to identify, prioritize, and design cost-effective spatial configurations of protected and conserved areas, which enables maximizing ecological benefits and minimizing social and economic costs and promotes the development of representative, connected, resilient, and equitable networks of PCAs. Marine Deguignet detailed the SCP process, which includes setting conservation objectives, assessing biodiversity features, evaluating pressures and threats, considering socio-economic factors (e.g., local communities’ reliance on natural resources for livelihoods), and designing an optimized conservation network.

Marine Deguignet introduced the importance of spatial conservation planning in identifying and recognizing OECMs

The analysis of protected area representation and gaps provides important references for the development of OECMs in China. Professor Lu Zhi from Peking University introduced that China’s protected area system covers about 18% of the terrestrial area. From the perspective of ecosystem representation, the coverage rate of protected areas for forest, grassland, and shrub ecosystems is below 30%, with significant gaps in densely populated areas in the eastern part of China. From the perspective of species representation, only 21.5% of the top 30% priority areas based on mammal and bird habitat assessments are within protected areas, with gaps in forests, farmlands, and urban habitats. These gaps are also reflected in the ecological conservation red lines, which cover about 30% of the terrestrial national territory. Lu Zhi noted that, in China, OECMs can play a positive role in filling existing gaps and increasing the protection of corridor areas. Also, in densely populated eastern and southern regions, OECMs can promote more inclusive and flexible conservation approaches that is compatible with human activities and support more bottom-up conservation initiatives.

Lu Zhi analyzed the gaps of protected areas and needs for OECMs in China

Lu Zhi analyzed the gaps of protected areas and needs for OECMs in China

Researcher Wang Wei from Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences shared his latest research findings, which shows that protected areas in China can effectively mitigate human disturbances to mammals, and the protection effect is positively correlated with the coverage rate of protected areas. Taking narrowly distributed species as an example, relatively good conservation effects can be achieved when the coverage by protected areas reaches around 29%, which is close to the current global conservation goals. Based on this, he suggested that important species distribution areas outside protected areas, especially those that cannot be established as protected areas due to complex issues such as land ownership, can be protected through the OECM approach, enhancing the connectivity of conservation network. He also explored the possibility of recognizing the transition zones of biosphere reserves as OECMs.

Wang Wei presented research findings on protected areas and OECMs

Wang Wei presented research findings on protected areas and OECMs

Terry Thompson, consultant at Paulson Institute, emphasized the important role of urban OECM networks as “stepping-stones” on the migratory routes of birds. He believes that cities like Beijing should create diverse habitats, such as wetlands, grasslands, and forests, as part of the OECM networks to support migratory birds. Researcher Guo Yinfeng from Marine Disaster Reduction Center, Ministry of Natural Resources also pointed out that migratory birds need a more connected conservation network. For migratory bird distribution points not covered by protected areas, conservation can be achieved through the OECM approach.

Terry Thompson shared thoughts on urban OECMs

Terry Thompson shared thoughts on urban OECMs

Guo Yinfeng discussed role of OECMs in migratory bird conservation network

Guo Yinfeng discussed role of OECMs in migratory bird conservation network

Opportunities and Challenges of OECMs

As an innovative conservation tool, OECMs have great potential in achieving biodiversity conservation goals and promoting sustainable development, while its implementation faces various challenges across the world.

Khalid Pasha, IUCN Asia Regional Coordinator, Protected Conserved and Heritage Areas, pointed out that OECMs support the inclusive conservation metrics under the 30×30 Target; create opportunities for the promotion of the IUCN Green List, sustainable financing, equity-based governance; legitimize community-led and faith-based conservation efforts; and encourages cross-sectoral cooperation (such as agriculture and extractives). However, OECMs also face many challenges, such as limited understanding of OECMs beyond environmental ministries; the need to explore the integration of OECMs into legal frameworks; insufficient capacity in documentation, monitoring, and free prior informed consent; and complex issues such as land tenure and legal recognition that need to be resolved. To address these challenges, IUCN supports countries in promoting the development of OECMs through various efforts, including facilitating national dialogues, promoting regional exchanges, and providing technical guidelines and capacity-building.

Khalid Pasha introduced the roles, opportunities and challenges of OECMs

Khalid Pasha introduced the roles, opportunities and challenges of OECMs

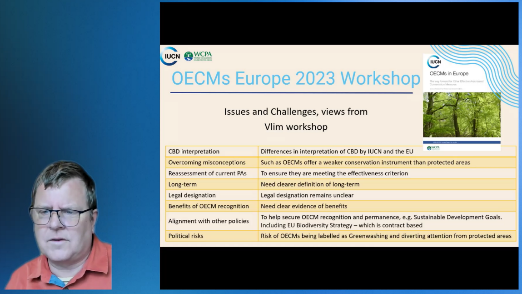

Olivier Hymas from University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and IUCN WCPA Europe OECMs focal point, highlighted several challenges in the implementation of OECMs in Europe. These include misconceptions that OECMs offer weaker protection than protected areas, complicated existing toolkits, insufficient capacity building, low public awareness of OECMs, and identification and reporting mechanisms that insufficiently engage non-state actors. It is worth noting that many European landscapes have been shaped by centuries of traditional-based management and use by local communities. However, the conservation contributions of these communities are not fully recognized and these rightsholders (e.g., landowners) are often overlooked in the identification and reporting of OECMs. Olivier emphasized that communication with communities should employ language that is accessible and comprehensible to them, avoiding overly technical jargon or terms that might evoke negative sentiments. For instance, in some communities, words like “biodiversity” and “conservation” carry negative connotations. There are also opportunities for the development of European OECMs, such as mapping IP&LCs landscapes, the European Restoration Law, advocating for inclusive conservation approaches, and strengthening regional exchanges between Euopre and culturally-rich regions such as China.

|

Hymas introduced Scotland’s exemplary practices in advancing OECMs and promoting community participation. Scotland first conducted a comprehensive assessment of its existing protected area system, finding it did not fully meet the definition of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Therefore, Scotland not only needed to improve its existing protected area system but also had to explore other ways, such as OECMs, to further increase conservation coverage. To this end, Scotland adopted a combined top-down, bottom-up, and horizontal approach, engaging in extensive dialogue with local communities. Using language based on traditional knowledge rather than modern science, they sought to understand the communities’ conservation governance systems and management plans, and learned along the way to involve all relevant stakeholders and rightsholders in the process. |

Olivier Hymas introduced issues and challenges of OECMs in Europe

Olivier Hymas introduced issues and challenges of OECMs in Europe

In China, the National Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan (2023-2030) (NBSAP) has identified OECM standard building and demonstration as a priority action project under “Priority Action 9: In-situ Biodiversity Conservation,” presenting opportunities for advancing OECMs. However, substantial challenges persist. Professor Lu Zhi from Peking University pointed out that the current management departments and mechanisms for OECMs in China are not yet clear, and there is a lack of relevant laws and policies. It is also necessary to explore criiteria and mechanisms suitable for China’s local conditions. Moreover, the Chinese name for OECMs has not been determined yet, and the civil cooperation mechanism also needs to be improved. Jin Tong, member of IUCN OECM China Expert Working Group, noted that the core challenges for OECMs in China at present is the lack of government recognition procedures and mechanisms. It is necessary to clarify the leading department, establish a cooperation mechanism, etc., to incorporate OECMs into China’s reporting system for fulfilling the 30×30 Target. Technically, formulating China’s OECM identification criteria and guidelines involves resolving multiple granular issues: defining conservation value, designing feasible monitoring frameworks for effectiveness and sustainability, and establishing dynamic management and withdrawal protocols. Guo Hongyu, Deputy Director of Greenovation Hub, based on their research on international marine OECMs, underscored that assessing management effectiveness and conservation effectiveness is the key to ensuring the long-term conservation effectiveness of marine OECMs. For areas with limited conservation history and difficult to measure the actual conservation outcomes, their effectiveness can be evaluated and predicted through the assessment of management effectiveness. However, the effectiveness assessment mechanism remains underdeveloped in many countries. She also noted that China needs to formulate policies and roadmaps for the identification of marine OECMs as soon as possible.

Jin Tong discussed the core challenges OECMs faced in China

Jin Tong discussed the core challenges OECMs faced in China

Types and Identification of OECMs

OECMs offer the potential to recognize existing conservation practices outside protected areas. Countries worldwide have various types of areas with the potential to become OECMs. This seminar also explored the types and potential of OECMs and how to better combine top-down and bottom-up approaches in the identification mechanism.

In Europe, several potential OECM types have been identified for further investigation, including privately managed conservation sites, military sites, spiritual, cultural or religious sites, high-conservation-value forests outside protected areas, riverine ecosystems with freshwater management, agricultural landscapes, and marine ecosystems. Heather Bingham introduced these types and emphasized that OECM identification should be conducted on a case-by-case basis. Attention needs to be paid on whether these areas are too small to have significant conservation value. She also suggested focusing on areas with identifiable biodiversity values in OECM identification and supporting existing conservation measures and governance systems that can produce long-term, sustained conservation outcomes.

Different countries have adopted various methods in the OECM identification process, each with its advantages and disadvantages, and have accumulated a wealth of practical experience. Olivier Hymas took Sweden as an example, whose reported OECMs are mainly voluntary set-aside areas (sustainably managed forests recognized by forestry certification systems). However, local community participation in the identification, management, and reporting of OECMs remains insufficient. Guo Hongyu shared the different models and experiences of marine OECM identification in Canada, India, and Japan. Canada first conducted a systematic screening and carried out individual recognition, quickly designating a batch of OECMs to meet the Aichi Targets. However, in later assessments, it was found that the conservation effectiveness of some recognized OECMs was not satisfactory. Therefore, when updating the standards, greater emphasis was placed on the effectiveness of conservation measures. Japan adopted a bottom-up application model: the government takes the lead in formulating recognition standards; enterprises, individuals, social organizations, universities, and other entities are encouraged to submit applications; and the government reviews the applications and grants certifications to qualified sites. Additionally, an incentive mechanism has been established to mobilize the participation of multiple stakeholders. India adopted a mixed mechanism of government-led identification and bottom-up application. However, the overall effectiveness of OECMs still needs to be further assessed and improved.

Guo Hongyu shared modes and experiences of marine OECMs identification in different countries

Guo Hongyu shared modes and experiences of marine OECMs identification in different countries

In China, many areas are already implementing management measures conducive to biodiversity conservation based on existing laws, regulations, policies, and plans. At the seminar, experts introduced and analyzed the potential of these areas to become OECMs and discussed how to better identify, recognize, and manage these potential OECM areas.

In China, the forestry and grassland authorities play a significant role in biodiversity conservation, undertaking responsibilities for the management of forest, grassland, wetland, desert ecosystems, protected areas, and terrestrial wildlife. Zhang Yan, Head of IUCN China Office, pointed out that although China’s current laws and policies do not explicitly mention OECMs or similar concepts, laws and policies such as the “Notice on Strengthening the Management of Ecological Conservation Red Lines (for Trial Implementation),” “Forest Law,” “Grassland Law,” “Wetland Conservation Law,” “Wildlife Conservation Law,” and “Regulations on Wild Plants Protection” all provide legal basis for conservation work outside protected areas. These laws and policies supports multiple types of potential OECMs, such as ecological public welfare forests, key wildlife habitats, important wetlands, and general wetlands, many of which are under the jurisdiction of forestry and grassland authorities. Zhang Yan shared the preliminary analysis results of the potential areas of various types of OECMs and focused on introducing the potential of state-owned forest farms as OECMs, which take the protection and cultivation of forest resources and the maintenance of ecological security as their main management goals.

Zhang Yan introduced potential types of OECMs in the forestry and grassland authorities and their potential

Zhang Yan introduced potential types of OECMs in the forestry and grassland authorities and their potential

Marine OECMs also have great potential to expand the effective protection area of the ocean. Associate Researcher Zhao Linlin from the First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, introduced that currently, global marine protected areas cover 8.3% of the ocean area, and the 202 OECMs recorded in the WD-OECM database contribute 0.11% of the marine protection area. In China, marine protected areas cover about 4% of the jurisdictional sea area, and marine OECM work is in its infancy. Due to the mobility, three-dimensionality, difficulty in detection, and systematic feature of the ocean, as well as the complexity of management entities and authorities, marine OECMs face greater challenges in demarcation, governance and management, and monitoring. Zhao Linlin also shared the identification criteria for marine OECMs in China, which specifically include four basic criteria: not legally approved as a protected area; effectively managed; achieving sustained and effective contribution to in-situ conservation of biodiversity; and associated ecosystem functions and services and other relevant values. He further analyzed whether various types of areas such as ecological conservation red line areas, important wildlife habitats, important / generic wetlands, fishery aquaculture areas, national tourist resorts, and ecological conservation and restoration areas meet the identification criteria. He indicated that except for the red line areas, which meets all the identification criteria, whether other areas meet the OECM standards still needs to be further confirmed in combination with specific local conditions.

Zhao Linlin introduced identification criteria of OECMs in China

Zhao Linlin introduced identification criteria of OECMs in China

In terms of the identification and recognition of potential OECMs supported by existing policies, Li Diqiang, researcher at Chinese Academy of Forestry, suggested a top-down demarcation approach for areas that meet the criteria of OECMs and have relevant legal basis, with specialized administrative departments, and monitoring and supervision departments. These areas could be recognized by the relevant administrative departments after approval from the competent authorities of the State Council. Guo Yinfeng stated that it is essential to thoroughly assess the similarities and differences between existing management systems (such as aquatic germplasm resource conservation zones and agricultural cultural heritage sites) and the OECM concept. Efforts should be made to integrate concepts such as ecosystem-based approaches and connectivity into existing management systems. He also believes that cultural elements need to be incorporated into the OECM framework.

“Pathways for OECMs in Forestry and Grassland Authorities” roundtable discussion

“Pathways for OECMs in Forestry and Grassland Authorities” roundtable discussion

Apart from promoting the potential of OECMs in policy-supported areas through a top-down approach, experts at the meeting also expressed their expectations for bottom-up initiatives for OECM application to encourage and mobilize the participation of the whole society in biodiversity conservation. Professor Lu Zhi introduced the results of the “OECMs China Potential Cases” collection campaign. Among the 46 identified cases, 22% were led by governments, while 78% involved communities, social organizations, private sectors, and universities, demonstrating the great potential of social forces in participating in OECMs. This campaign, as an initial attempt for bottom-up OECM application mechanism, has accumulated valuable experience for future OECM application and identification work.

Regarding the identification mechanism, considering that potential OECM areas in China involve different competent authorities, Liu Wenhui, Senior Engineer at Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences, proposed two possible mechanisms for OECM identification and recognition. The first is to have multiple departments jointly issue recognition criteria and measures, and authorize the establishment of an OECM review committee to conduct OECM identification and assessment. The second is for each department to formulate its own recognition measures, with the environmental department, as the leading authority for the implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity, consolidating best practices.

Liu Wenhui shared thoughts on OECMs identification mechanisms

Liu Wenhui shared thoughts on OECMs identification mechanisms

Mobilizing Multi-stakeholder Participation in OECMs

OECMs provide a broad platform for various sectors of society to participate in biodiversity conservation. How to better motivate and mobilize the enthusiasm of all parties is an important issue to be addressed.

In terms of OECM criteria, experts at the seminar emphasized the importance of ensuring that these criteria are both rational and encouraging. On the one hand, the standards must be scientific and feasible. On the other hand, moderately relaxing the standards can encourage more entities to participate in biodiversity conservation and cultivate a diverse stakeholder base. Fang Zhi, former Deputy Secretary-General of China Environmental Protection Foundation, suggested that the criteria and threshold for OECMs should not be set too high to encourage broader participation from the society. Guo Yinfeng stressed that the formulation of standards should fully consider the national conditions and legal systems of different countries and sectors to ensure their applicability and user friendliness. He also mentioned that while the original text of the 30×30 target uses the term “ensure,” the Chinese delegation proposed adding “enable” during negotiations, hoping to incorporate and support conservation practices of varying levels of maturity through OECMs, thereby gradually enhancing conservation effectiveness.

Fang Zhi discussed the role of OECMs in encouraging non-state actors to participate in conservation

Fang Zhi discussed the role of OECMs in encouraging non-state actors to participate in conservation

The supervision and management of OECMs should also avoid overly strict mandatory requirements to prevent discouraging practitioners. Luo Ming, Researcher at Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Center, Ministry of Natural Resources, believes that OECMs should serve as an encouraging tool rather than a mandatory regulatory measure, maintaining their voluntary and flexible nature to promote broader application and practice. She cited examples such as the protection of fengshui forests and subsequent development of bird-watching ecotourism in Shimen Village, Shangrao, Jiangxi province, the natural restoration of abandoned mines in Czech Republic, and organic tea gardens in Lishui, Zhejiang province, to discuss the potential for various sectors of society to participate in OECMs in diverse ways. Liu Wenhui suggested that OECMs should undergo regular assessments, have withdrawal mechanisms, and implement dynamic management to encourage greater participation.

Luo Ming shared views on the potential for various non-state actors to participate in OECMs

Luo Ming shared views on the potential for various non-state actors to participate in OECMs

The establishment of appropriate incentive mechanisms addressing the needs of relevant stakeholders is also critical. Heather Bingham believes that for OECM practitioners, the benefits of being recognized as an OECM mainly depend on how state and non-state actors choose to support OECMs. Wang Wei said that in the implementation of OECMs, it is necessary to balance the interests of multiple parties, establish an effective coordination mechanism, and at the same time explore the combination mode of conservation and community sustainable development, such as promoting local economic development through ecotourism. Olivier Hymas observed that, in the European context, the incentives required by the private sector and local communities differ significantly. For instance, Sweden supports large forestry companies and large-scale farms with voluntarily conservation actions through funding mechanisms such as conservation easements. However, for many communities and small-scall farmers, compared with financial support, they need more recognition and acknowledgment of their conservation contributions. Khalid Pasha pointed out that companies can enhance their corporate social responsibility (CSR) by investing in OECMs or carrying out OECM practices on their land. Also, further exploration is needed on how to leverage OECMs to incentivize sustainable and biodiversity-friendly practices in production landscapes and seascapes (e.g., agriculture, fisheries). Jin Tong noted that building a platform for peer-to-peer sharing and exchange through OECM case collection initiatives is also a potential incentive for conservation practitioners.

The implementation of OECMs also requires broader public participation. Terry Townshend underscored the importance of raising public awareness of OECMs through education and outreach, saying, “In implementing the GBF, we can’t rely on professional conservationists alone. We need everyone to be a conservationist.” He cited citizen science data as pivotal to conserving Beijing’s Houshayu Wetland, while the “Embassies for Nature” initiative in Beijing supports managing embassy green spaces in a more nature-friendly way. These cases all show the important role of public participation in OECMs for biodiversity conservation. By giving the public a sense of participation and responsibility toward global targets, broader conservation actions can be catalyzed. He noted that establishing a concise, attractive Chinese name for OECMs is a key issue in promoting public understanding and participation.

“China-Europe OECMs Policy Dialogue” roundtable discussion

“China-Europe OECMs Policy Dialogue” roundtable discussion

Exploring OECM Pathways to Promote Biodiversity Mainstreaming

At the seminar, Chinese and international experts engaged in in-depth discussions on key aspects of OECMs, including enabling conditions, identification, monitoring, reporting, and strengthening. They also shared valuable insights into the potential pathway and strategies for OECMs in China, agreeing that OECM is an important tool for promoting biodiversity mainstreaming across the whole government and society. A combination of top-down and bottom-up collaborative mechanisms is needed to fully leverage the dual strengths of government guidance and social participation, driving the formation of a more inclusive and sustainable conservation network.

From a top-down, government-guided perspective, the development of OECMs requires a systematic identification and assessment of the potential of various policy-supported areas (such as ecological public welfare forests and important wetlands) to qualify as OECMs. This requires integrating OECM principles into existing management and monitoring mechanisms, fostering cross-departmental collaboration, and scientifically guiding OECM spatial planning through spatial conservation prioritization and gap analysis to maximize ecological benefits.

From a bottom-up, social-participation perspective, there is a need to further enhance the awareness and attention of all sectors of society to OECMs, stimulate voluntary conservation actions, and encourage the enthusiasm of conservation practitioners through multiple aspects such as less stringent criteria design, dynamic management, and external support. Through joint efforts from the government and diverse stakeholders, incentive mechanisms—encompassing financial support, policy recognition, technical assistance, and capacity building—need be explored to reduce participation barriers, enhance conservation motivation, and thus foster sustainable conservation models.

Professor Lu Zhi emphasized in her concluding remarks that the key to OECMs lies in intrinsic motivation for conservation. It is necessary to clarify the benefit-sharing mechanism to safeguard and encourage such voluntary commitment. By enabling OECMs through multifaceted approaches, their conservation outcomes can be progressively enhanced to ultimately meet compliance standards of the 30×30 target. Demonstrating the tangible benefits of OECMs to governments and communities via a series of practical cases will catalyze top-down and bottom-up synergies, jointly advancing the establishment and improvement of OECM mechanisms.

After introducing the purpose, activities, deliverables, and collaboration mechanisms of the OECMs Policy Dialogue Project, she also expressed hope that this project would facilitate further international and domestic policy exchanges, accelerating OECM implementation in China through multi-stakeholder collaboration.

Lu Zhi delivered concluding remarks

Lu Zhi delivered concluding remarks

Seminar group photo

Seminar group photo